The village square was dead but for a few cats and the distant cackle of free roaming chickens out for their evening constitutional. It was early November. Kyria Popi, a portly woman dressed in simple dark blue and black and straddled in a well-worn apron, waited for us in the doorway. We sat down under a hovering old sycamore and soon were treated to one of the best meals I had ever had in Greece: Crisp, fried zucchini blossoms served with creamy garlic sauce, incredibly flavored runner beans, lightly stewed with whole, fresh plum tomatoes and mint, pan-fried wild goat, rabbit casserole with vinegar, local cured pork cooked with eggs, snails seared with vinegar and rosemary, and a wild greens omelet called sfouggato.

Crete is the best eating place in Greece, a treasure trove of wild foods and deeply rooted cooking traditions, but finding a great meal here on the Mediterranean’s fifth largest island is often a matter of going out of the way for it, off the tourist track, into the villages to places that are so simple you are almost afraid to walk inside. But it is in the villages, and oftentimes in the village coffee shack, that you’ll find the most vibrant examples of the mother of all Mediterranean cuisines.

We had actually gone down to enjoy a yearly tradition, the lighting of the kazania, or stills. November is the time of year when artisan wine makers bring their residual skins and pulp, which are leftover after the grape pressing two months earlier, to a local still, usually run by a private, licensed local distiller and rented, services included, to anyone who wants to produce his own fire water. In Crete that spirit is called raki, and its distillation is cause for celebration. The process takes several hours, and people bring food and invite friends. On that day’s menu the piece de resistance was a sack half full of potatoes, baked whole in embers, smashed open with the pound of a fist (everyone pounds his own potato) and seasoned with nothing but sea salt and fresh olive oil. It was one of the most sating things I have ever tasted, washed down, of course, with what might, in other nations, be known as moonshine. One can find about such festivities by asking the local hotelier, who is more than likely to have arranged for the distillation of his own raki from one such local still.

I think of Crete as an island with two distinct halves, the eastern half, from Herakleion to Sitia, and the western half, from Rethymnon to Kissamos. The north and south on either side have more in common than either extreme. In fact, there are distinct culinary and cultural differences between eastern and western Crete. On our foray to the island we stayed in a small hotel outside of Rethymnon and made day trips centered around food. The roads are, for the most part, good and crossing the island from east to west, or north to south, while time-consuming, is not difficult.

Once you are away from Crete’s bustling coast, and especially in the off seasons, the island pulses to a different rhythm. One of my most memorable experiences was driving from Herakleion southwest over the mountains to Sfakia, in search of a local sweet cheese pie, and stopping dead in my tracks as the view of the Libyan sea expanded before me. The feeling of being on a lone frontier overwhelmed me. Then, like an apparition from some long gone era, a local shepherd with his flock of 30 or so sheep rose from a mountain path. He was 60ish, tall and lean, mustachioed, and dressed in the characteristic black shirt, pants, boots and thick woollen cape that shepherds wear. As he leaned on a long, knobby hand-carved cane we asked to take his picture. He stiffened, and indicated that we dare not, then turned around and disappeared back down the path, too proud of his heritage to be taken for a mere relic. Many old-timers, I later learned, have an almost superstitious anathema to pictures, as though by capturing them on film you are snatching away a little bit of their spirit. We made our way onto Sfakia, and in what seemed like every small taverna along the town’s main road we stopped for a strong Greek coffee and a taste of the cheese pie sfakiani pita of local fame. It is something between a crepe and a pancake, filled with a delicious, soft, sour cheese called xynomyzithra, pan-fried and served with a generous drizzling of thyme honey.

Within the general radius of Hania, again upon the recommendation of a local friend, we drove east this time, for about 40 miles, in order to get to the village of Prases to visit Katina Kotsaki at her eponymous family-run cafeneion. I had called her in advance, which is advisable if you are interested in sampling more than the daily fare she cooks up for her own family. That day the menu was no disappointment. We dined on some of the best grain dishes I’ve ever found on the island, especially the rice pilaf fragrant with local clarified butter called staka, and the hondros, cracked wheat, which was cooked together with snails, another Cretan staple. Her kallitsounia, pastries filled with wild greens and cheese, and her potatoes were perfect: both fried in olive oil over a wood fire and worth 40 miles’ driving to nibble on.

From Rethymnon, the drive east along the highway is straightforward, and we decided to head well past Herakleion to enjoy “brunch” a la Crete in a tiny roadside place called Yiorgia’s, in Tarmaros, not too far from Malia. Yiorgia is a simple cook whose repertoire doesn’t exceed a handful of dishes, among them the sunnyside up eggs drizzled with lemon juice and served on a pool of her own delicious chartreuse olive oil. She brought us another Cretan home-made specialty, tiny cracked green olives flavoured ever-so-delicately with bitter orange juice.

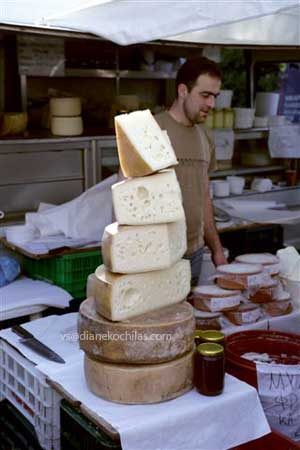

We spent the afternoon driving around some of the villages in Lasithi, one of the main farming plateaus in Crete, and settling for our evening meal in Hersonissos at a hidden gem called Stenakis mezethopoleion, which was really nothing more than a glorified shack surrounded surrounded by olive and mulberry trees and situated about halfway up the peninsula, which is what Hersonissos means in Greek. Hersonissos, together with Malia, is one of the most egregiously touristy places on the island. Both villages, though, are ghost town in the off season. The home cooking here was exceptionally good. The family runs a rabbit farm, so it goes without say that rabbit is the main fare here. My favorite dish was the olive-oil-fried rabbit, “extinguished,” as they say in Greek, with red wine. If rabbit doesn’t sound appealing, it’s worth it just to come for the fries, silver-dollar sized and cooked in the island’s ubiquitous olive oil. We were given a wedge of excellent kefalograviera, a local sheep’s milk cheese and served a bowl of pale green mashed fava beans together with a few shots of the ubiquitous fire water. At then end, to prepare for the long ride back, we finished with a spoonful of candied bergamot and quince, two of Crete’s many preserved fruit dishes.

Greeks consider Crete their culinary cradle, a place where the food traditions of the whole Aegean culminate. The island has the most well-defined cuisine of all Greek islands. More than anywhere else, the cooking of Crete is shaped by the seasons and by a well-honed sense of versatility, so that the same simple ingredients are used again and again to create a whole spectrum of different dishes. At any time of the year, the food is memorable, as long as you are sampling the real thing.

Information:

All the tavernas listed below are mom-and-pop kind of places, open for lunch and dinner, beginning around 11 am and usually closing when the last customer leaves. Most do not take credit cards. The menu usually changes daily and is almost always seasonal, with cooks going out to pick their own greens and oftentimes serving up eggs from their own chickens and other exclusively local food. Local customers call beforehand to order what they want to eat, something that can be done from the hotel. Smoking is allowed.

Taverna Patrelantonis, right on the sea with a view of the snow capped Lefka Ori Mountains in the background. The taverna is in the small village of Marathi, in Akrotyri, about 30 kilometers east of Hania on the airport road, and specializes in fresh, local fish and a few daily local specials. Cuttlefish with wild fennel and olives; char-grilled cuttlefish stuffed with feta and onions; dried fava casserole (4E); grilled octopus (7E); sea urchin salad (9); and Cretan barley rusk and tomato salad (2.40E). In the winter Petralantonis opens only on weekends, but from May to October the taverna is open every day, for lunch and dinner. General information: Tel. (30) 28210 63337

Taverna Milia in Vlatos, Kissasmos, is located in a lovely agricultural compound in a renovated village on the far western side of Crete. Dishes are seasonal and made with ingredients grown on the compound’s land. Local spring and summer fare includes eggplant, vegetable and potato casserole, 5.50 E; Rabbit stuffed with a soft, local sheep’s milk, myzithra, 7E; and lamb baked with zucchini, 7.50E. General information: (30) 28220-51569

One of the more sui generis places on this itinerary is the Cafeneion tou Kotsaki, in the town of Prases, about 30 kilometers south of Hania, perched about 500 meters over a river and surrounded by mountain terrain, gorges, and lush foliage. It’s best to call from the hotel and to order whatever country dish or dishes you would like to try, from hand made savory pies, to artichoke, zucchini and herb frittatas, to all sorts of local meats—maiknly goat and lamb—which is sold by the kilo (around 8E a kilo) and roasted, cooked up in casseroles, grilled, whatever. Mrs. Kotsakis does all the cooking. English is lagging, but Kotsakis’ cafeneion is the kind of place that gives you a peek at the real Crete, well worth the drive. General information: (30) 28210 77 901.

Cafeneion tis Caliopes is another traditional roadside cafeneion and a favorite among locals. It’s best to call to let Caliope know you are coming. You can also order in advance so that your meal is ready upon arrival. Caliope cooks in a tiny place in the historic town of Potamous, in Amari, about a 45 minute drive above Rethymnon. Depending on the season, the things to try are: green beans with fresh plum tomatoes (3-4 E), her pan-fried cheese and greens pies (3-4 E), and the hot cheese and honey pie that she brings out at the end (3-4 E). General information: 30 28330 61 440/ 61 285

Yiorgia, in Tarmaros, on the national road about one kilometer east of the Malia archeological site, is open all year round, from breakfast through dinner. She is one more in the league of heroic women cooks in Crete. The menu here changes daily, “as if I was cooking at home,” she says. Hand cut Greek fries in Cretan olive oil, 2E; green bean ragout and chick pea soup, 3E; local farm eggs, fried or in omelets, 2E; homemademeatballs, 3E; lamb baked with tomato sauce and served with local pasta, 6E. General information: (30) 28410 71 698

Stenakis Mezedopoleion is on the high end as far as small, Cretan eateries go, located in Hersonissos, arguably the most popular tourist area on the island. Rabbit sautéed in olive oil, 6E; those famous Greek fries, 3E, homemade spoon sweets, 2-3E. General information: (30) 28970 25 406